Agnès Varda and the French New Wave

Editor’s Note: Agnès Varda was born May 30, 1928. To celebrate her birthday, Dylan explores how Varada’s work influenced and was influenced by the French New Wave film movement

By Dylan May

The French New Wave is a film movement that began in the late fifties and early sixties, particularly in France, and soon began to influence the greater cinematic lexicon. Jean Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, and Francois Truffaut were some of the filmmakers responsible for the movement and its ultimate popularity. Eventually, the New Wave movement would reach America and influence the likes of Alfred Hitchcock.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless

One of the key characteristics of the French New Wave is its rejection of past filmmaking, instead swapping in more experimental and avant-garde techniques. This experimentation can be seen in Breathless, directed by Jean Luc Godard, where he used jump cuts in a continuous scene. These jump cuts gave the scenes an odd electricity, creating an additional rhythm that captivated some audience members and confused others. With Godard’s Breathless, the departure from the old ways of filmmaking was sudden and swift, causing a very mixed reaction from movie-going audiences. The jumpy editing and the ‘realistic’ view on romance had French and American audiences uncertain how they felt about the film.

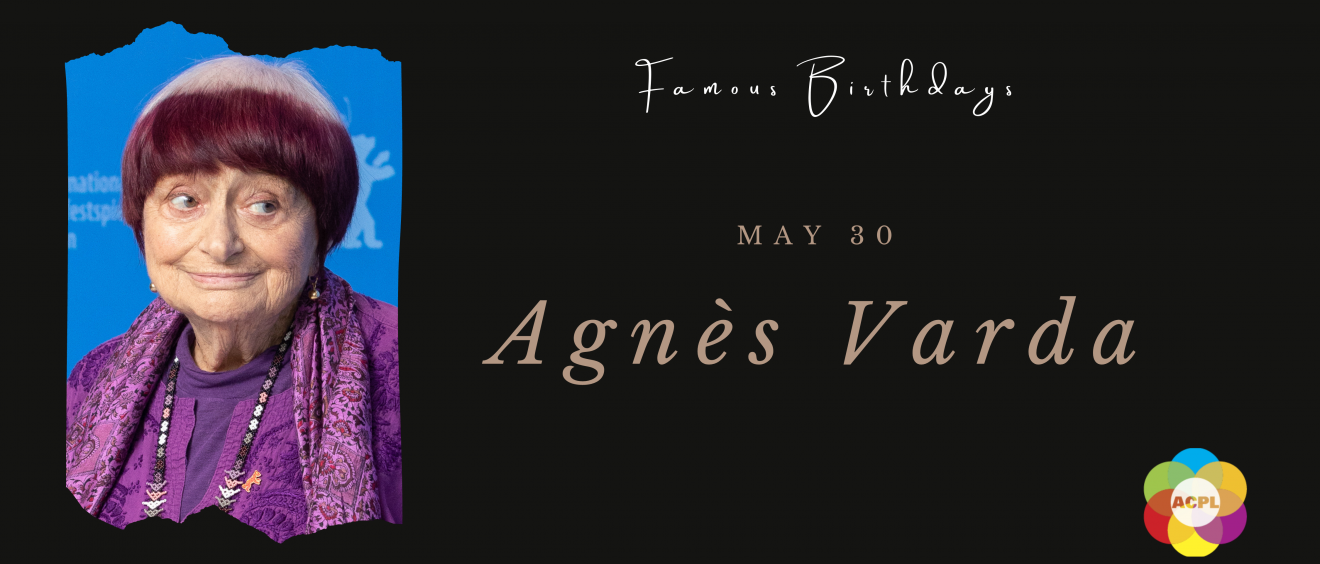

In part with the experimentation of film techniques, New Wave oftentimes took on heavy political topics, often addressing social injustice and taking on societal norms. Agnès Varda, born May 30, 1928, was one of many directors that often had these political messages, which cemented her in the zeitgeist and became an important part of cinematic history. Varda had no prior experience in film or much film knowledge, stating that she hadn’t even seen many films up to that point only finishing her first feature film at the age of twenty-six, La Pointe Courte. Working as a photographer, Varda was inspired while taking pictures in her hometown of Sète. Observing the economic turmoil that had hit, as well as political strife, Varda combined elements of her own life into the script.

In La Pointe Courte, Varda follows the lives of Lui and Elle, depicting how a marriage already on the rocks and the struggle of a world crumbling around them can unwind a relationship and bring it together. Following the success of this film, Varda followed it up with a smattering of shorts until she made her second feature film Cleo from 5 to 7. This follow-up would become arguably Varda’s most popular. Cleo tells the story of a singer who becomes more and more convinced that she has cancer, seeks the help of a doctor who has her take a series of tests, the results of which take a long time to come in. This causes Cleo to spiral more, becoming more and more panicked and convinced that she is ill. Nominated for a Palme d’Or award at the Cannes Film Festival, this film brought Varda renowned acclaim, going on to even be considered one of the greatest films ever made.

In La Pointe Courte, Varda follows the lives of Lui and Elle, depicting how a marriage already on the rocks and the struggle of a world crumbling around them can unwind a relationship and bring it together. Following the success of this film, Varda followed it up with a smattering of shorts until she made her second feature film Cleo from 5 to 7. This follow-up would become arguably Varda’s most popular. Cleo tells the story of a singer who becomes more and more convinced that she has cancer, seeks the help of a doctor who has her take a series of tests, the results of which take a long time to come in. This causes Cleo to spiral more, becoming more and more panicked and convinced that she is ill. Nominated for a Palme d’Or award at the Cannes Film Festival, this film brought Varda renowned acclaim, going on to even be considered one of the greatest films ever made.

Varda then directed and wrote Le Bonheur, a film that greatly followed in step with the French New Wave, which examined patriarchal France and its effect on women and marriage. The film follows François, a young carpenter and father of two, who begins a romance with a new woman. On an outing to the park François’ wife, Theresa, asks him why he is so happy. Admitting he is having an affair, François tells her that he is not unhappy with her but instead has gained more happiness with his new lover. He and his wife then make love, François falls asleep, and he later awakes to find Thérèse gone. As he searches for her, he comes upon her dead body being retrieved from the lake. Rather inhumanely, François mourns his wife for a short period then marries his mistress and finds happiness again with his new family.

Possibly one of the more shocking endings of Varda’s films, Le Bonheur has had much discourse surrounding what Varda intended the film to mean. In an essay written about the film for the Criterion Collection, Amy Taubin writes, “ Even more challenging than her female characters are the questions Varda poses about female subjectivity. Who speaks for women’s experience and subjectivity in a society—global patriarchy—where women are conditioned from birth not to speak for themselves? Thérèse and Émilie in Le Bonheur are extreme examples of women who do not speak, women who repress the knowledge of their own feelings and desires, lest they come into conflict with their husband’s or lover’s “happiness.”’

Agnès Varda’s Le Bonheur

As a feminist, Varda often commented on the female perspective and how women live their lives, specifically in a suppressive environment. Thérèse’s experience is centered entirely around her husband and family, similar to many women at the time. Once Therese dies, Emilie takes her place, assuming the happy housewife routine and completing Francois’ need for a happy nuclear family.

Varda received an honorary Oscar in 2018, during the 90th annual awards. Throughout her sixty-four-year career, Varda directed a total of 60 films and shorts, a majority of which she also wrote. Not only making her impact in French New Wave, she also became a staple in auteur theory. Varda passed away at the age of 90 in Paris on March 29, 2019.